South Asian countries can support PPPs to introduce new antibiotics responsibly

Author

Author

- admin / 2 years

- 0

- 6 min read

Author

Given that AMR poses a significant health burden, particularly among vulnerable populations, and those with limited access to quality healthcare, India has implemented several important strategies to combat the challenge.

India faced a severe health crisis as antimicrobial resistance (AMR) claimed 297,036 lives, with 1.04 million deaths associated with it, in 2019. Bacterial infections and sepsis caused 1.79 million and 2.99 million deaths respectively, reflecting the dire threat of AMR. The country also reported 7.09 deaths per 100,000 from resistant tuberculosis, outpacing the South Asian average of 6.51.

In an exclusive email interview with First Check, Prof. Ramanan Laxminarayan, one of the authors of The Lancet Series on Antimicrobial Resistance and the founder and president of the One Health Trust (OHT), said, “South Asian countries, India included, are doing a lot to reduce the burden of infections in the region. In the Lancet series, we present clear targets and recommendations for amplifying this response with concerted efforts like vaccination, improved water sanitation and hygiene, and infection prevention and control.”

Governments of South Asian countries, he noted, can help increase access to antibiotics by supporting public-private partnerships (PPPs) to introduce new antibiotics responsibly and at affordable costs. This can also help facilitate greater regulatory harmonisation to lower registration costs and accelerate access, he said.

The challenge

The inappropriate use of antibiotics in South Asian countries, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic, exacerbated the AMR burden in the region. Due to the limited availability of antiviral treatments for the infection, physicians often resorted to prescribing antibiotics to manage symptoms. This led to broad-spectrum antibiotic prescriptions, and over-the-counter availability of antibiotics through unregulated pharmacies also fuelled this challenge.

As of today, AMR is associated with a significant health burden, particularly among vulnerable populations, and those with limited access to quality healthcare. “Newborns and older people in India are particularly vulnerable to AMR, considering the high prevalence of diseases often linked to the overuse and misuse of antibiotics,” stated OHT researchers.

The incidence of lower respiratory tract infections, for example, is 9,682.57 per 100,000 live births among neonates and 176.68 per 100,000 among ages 65-69 in India. Similarly, the incidence of diarrhea is 535.80 per 100,000 live births among neonates and 176.68 per 100,000 among ages 65-69. “People with chronic illnesses are also impacted by AMR. For example, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) accounted for 9.08 per cent of deaths in India; patients with COPS are severely affected by secondary infections that are resistant to treatment,” the researchers added.

Indian example

While India has implemented several strategies to combat AMR, the most important one is the development of a National Action Plan (NAP) for AMR (2017-2021). Authorities have been working towards mitigating AMR through strategic measures, such as, improving awareness by effective communication, education, and training, promoting surveillance in human health and animal/food sectors, reducing the incidence of infection through effective IPC measures, and investing in research and innovations through new medicines and diagnostics, to develop alternative approaches to manage infectious diseases, and to ensure sustainable resources for containment of AMR, among others.

According to the OHT researchers, following are the key initiatives contributing to the mitigation of AMR in India:

- Health priorities under G-20 Presidency: As part of its G-20 presidency, India identified three health priorities, one of which emphasises a ‘prevention, preparedness, and response’ approach to health emergencies with a focus on AMR and the One Health framework.

- Inter-sectoral coordination committee on AMR: This Committee emphasises the importance of coordinated multi-sectoral actions to address AMR, highlighting the need for collaborative efforts across various sectors.

- AMR surveillance and research network (AMRSN): The Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) established AMRSN, a network of 30 tertiary care hospitals (private and public), to generate evidence and track trends and patterns of drug-resistant infections nationwide.

- National guidelines for infection prevention and control: India introduced new national guidelines for IPC in healthcare facilities to enhance patient safety and equip health workers with the necessary skills to prevent and control infections. These guidelines address current and future threats from infectious diseases like Nipah and Ebola, strengthen health service resilience, combat AMR, and improve overall healthcare quality.

- Regulating sales of prescription medicines: India launched the ‘Medicines with the Red Line’ campaign in 2016 to raise public awareness about the responsible use of antibiotics. The campaign emphasised the importance of taking antibiotics only when prescribed by a doctor and completing the course. Additionally, a directive issued by the Director General of Health Services in January 2024 urged pharmacists to adhere to schedule H and H1 of the Drugs and Cosmetics rules, prohibiting over-the-counter sales of antibiotics to promote judicious use and reduce AMR.

- Ban on colistin in food-producing animals: The Union Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MoHFW) banned the use of the antibiotic colistin in food-producing animals, poultry, and aqua farms. This measure aims to curb the growing problem of AMR in humans that can arise from the use of antibiotics in animals.

- Standards for antibiotics in milk: The Food Safety and Standards Authority of India (FSSAI) established standards for antibiotics and veterinary drugs in milk and other products under the Food Safety and Standards (Food Products Standards and Food Additives) Regulations, 2011. This includes setting tolerance limits and requiring all food business operators involved in processing and selling milk to comply with these regulations.

- Indian Network for Fishery and Animals Antimicrobial Resistance: The Indian Council of Agriculture Research (ICAR) and the Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) facilitated the establishment of INFAAR, a national network of veterinary laboratories. This network aims to ensure safe food production that is free from the risk of transmitting AMR to humans. Currently, INFAAR includes 20 laboratories and seeks further expansion.

The way ahead

Based on the Global Database for Tracking Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR), Country Self-Assessment Survey (TrACSS) report, significant strides have been made in the South-East Asia region (SEARO) regarding hospital infection control. However, implementation challenges remain.

As of 2023, four countries – Sri Lanka, Indonesia, Thailand, Maldives – in the region had a National Infection Prevention and Control (IPC) programme that aligns with the WHO IPC core components guidelines. Bhutan, Nepal, and Timor-Leste in the SEARO have WASH (Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene) and IPC guidelines in their healthcare facilities, although these have not been fully implemented. Bangladesh, India, Myanmar have national IPC programmes with operational plans and disseminated health care IPC guidelines. However, only selected health facilities are implementing these guidelines.

Overcoming barriers to access to existing and new antibiotics in South Asian countries requires a comprehensive approach involving PPPs between governments, international organisations, drug developers, pharmaceutical firms, and healthcare providers, maintain researchers. Furthermore, expanding and implementing universal healthcare coverage can significantly reduce patients’ out-of-pocket payments and improve access to essential medicines, including antibiotics.

“It is important to note that efforts to improve antibiotic access must come with stewardship plans,” asserted OHT researchers, “to ensure timely and appropriate access, where a patient receives the correct drug at the right time.”

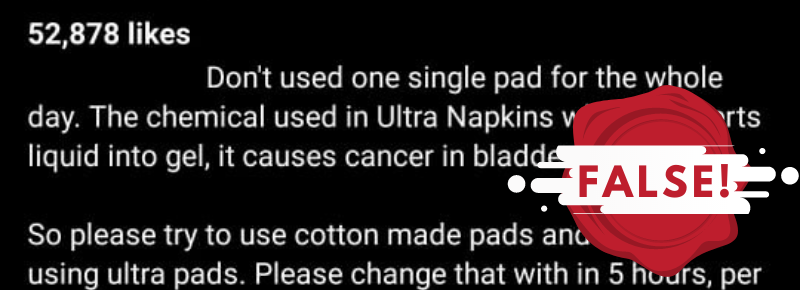

Read more: Fact-check: Antibiotics are not always needed to treat sinusitis