At just 22, Arijit Gupta, a postgraduate student at Jamia Millia Islamia, navigates a world defined by endless assignments and tight deadlines. The constant pressure to excel has left him exhausted and mentally drained.

“As a master’s student, work pressure is expected, but sometimes it gets too much and you are so overwhelmed that you lose track of anything else. Academic and work pressures have often made me fall sick. Often it has happened that I didn’t even have the time to recover,” says Arijit.

The mental stress, he says, takes a toll on him. “Mentally, I stay exhausted most of the time due to overburdened assignments and work. More than physical exhaustion, mental exhaustion takes away more energy. It also induces a lot of stress that otherwise could have been avoided. Also, regarding classmates and workspaces, the environment becomes extremely toxic at times,” he added.

Arijit is one among millions of students across India, navigating a hyper-competitive education system that leaves little room for error. Students grapple with relentless workloads, high-stakes entrance exams, and the crushing weight of parental, peer, and self-imposed expectations.

While government programs like ‘Manodarpan’ aim to provide counselling, limited access and persistent pressure mean that most students continue to cope in silence. The combination of intense competition, societal pressure, and lack of institutional support has contributed to rising rates of mental health issues and student suicides, underscoring the urgent need for a holistic approach that values well-being alongside academic success.

According to a recent cross-sectional study, which analysed data from 80 documented suicide cases among IIT JEE and NEET aspirants, alarming rates of suicide were observed among these students in India, emphasising the urgent need for targeted mental health support and intervention strategies.

The dark side of competitive coaching

Every year, millions of students across India appear for high-stakes entrance exams, yet only a fraction succeed. In 2025, 1,80,422 candidates appeared for both Paper 1 and Paper 2 of JEE (Advanced), with just 54,378 qualifying. Similarly, around 22.09 lakh students took the NEET UG exam this year, slightly fewer than the 23.33 lakh who appeared last year, with only 12.37 lakh clearing the test. Coaching hubs like Kota have become grim symbols of the pressures faced by students.

Dr Nimesh Desai, Senior Consultant Psychiatrist and former Director of IHBAS, explains the heightened pressures and the mental health tolls in context: “Adolescence, combined with critical exams, creates immense pressure. The rapid pace of societal change, growing competition, and aspirational middle-class expectations all contribute to this strain. The social importance attached to marks—‘Bache ne kitne marks laye’—adds to the stress.”

He also highlighted parental influence on mental health as well: “If I don’t become a doctor, I will make my daughter a doctor. Unknowingly, parents add pressure, trying to fulfil their own aspirations through their children.” Dr Desai emphasised the systemic risks, noting that mental disorders such as bipolar depression, schizophrenia, OCD, and recurrent depression often manifest between ages 15 and 25. “Early identification and detection of mental disorders can itself prevent crises,” he said.

“Besides psychological and scientific factors, there’s a strong business angle. Coaching centers charge lakhs for courses, and even if students want to return home, parents have often already paid huge amounts. This creates an environment where students’ failures are monetised, adding to stress,” Dr Desai also pointed out.

Inside the pressure cooker of premier institutions

Not only aspirants, even those who finally make it into India’s most prestigious campuses after years of relentless hard work often find themselves trapped in another tunnel of pressure.

As per a Lok Sabha answer in August 2023, a total of 91 student suicides were reported across premier institutes between 2018 and 2022. Of these, IITs accounted for 32 cases, NITs 21, Central Universities 20, AIIMS 11, IIMs 4, and IISERs 3. The numbers reveal troubling fluctuations—21 suicides in 2018, 20 in 2019, 13 in 2020, 10 in 2021, and then a sharp jump to 27 in 2022.

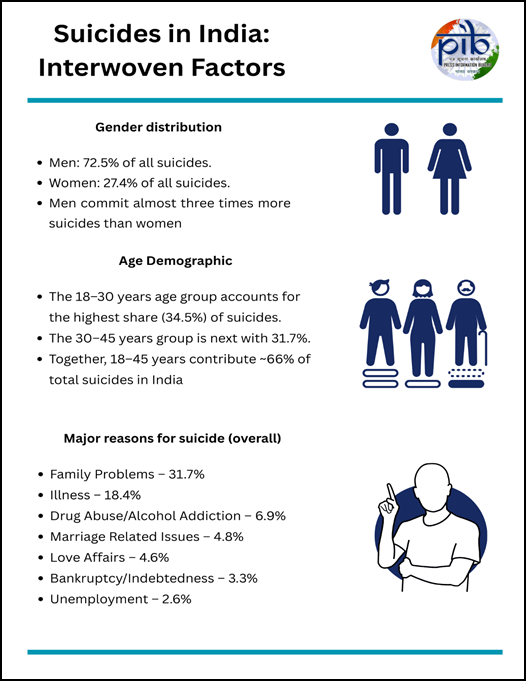

And it is not just the elite institutes—the scale of India’s student stress crisis is staggering. In 2022 alone, over 13,044 students died by suicide, according to the National Crime Records Bureau, with 2,095 deaths due to failure in examinations. Over the past decade, student suicides have risen at twice the national suicide rate, increasing by 4% annually compared to 2% overall. Students now account for 7.6% of all suicides, with the majority occurring in Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu, Madhya Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh, and Jharkhand, which together comprise nearly half of all cases.

In fact, a large-scale survey of 8,542 students across 30 universities in nine Indian states has highlighted the alarming prevalence of mental health challenges among college youth. The study found that 18.8 per cent of students had considered suicide in their lifetime, and 12.4 per cent had thought about it in the past year, while 6.7 per cent had attempted suicide at some point.

One-third (33.6 per cent) of participants reported moderate to severe symptoms of depression, and nearly one-quarter (23.2 per cent) experienced moderate to severe anxiety. Among those who had suicidal thoughts, only 38.1 per cent disclosed them to someone—most often to friends. These findings underscore the urgent need for targeted interventions to address depression, anxiety, and suicidal behavior among India’s student population.

The roots of this crisis lie in the very structure of India’s education system. Parents often see academic success as the only path to stability, and children internalise this belief from an early age. With scarce jobs and fierce competition, exams become impossibly high-stakes events. A study published in the International Journal of Education and Finance Management underlines how this hyper-competitive culture transforms schools and colleges into pressure chambers, eroding the joy of learning. It concludes that in today’s complex social landscape, success is influenced by a multitude of factors, including education, skill sets, opportunities, and more.

While academic excellence can boost one’s chances, it is not the sole determining factor. The current system’s emphasis on marks creates undue pressure, overshadowing the importance of holistic development.

Sumit Singh, a second-year MA student at AJK MCRC, said that moving from undergraduate studies to his master’s was a shock. Classes now run until 5 pm, with readings and assignments spilling into weekends. The constant workload, Sumit says, leaves him feeling overwhelmed and burnt out.

He believes the Indian education system burdens students with tasks that offer little practical training, encroaching on personal space and mental well-being.

In fact, a 2022 study examined the impact of academic and family stress on students’ depression levels and subsequent academic performance, using SEM analysis on data from undergraduate and postgraduate students. Results showed that academic and family stress significantly increased depression, which in turn negatively affected academic performance.

“Students’ high rates of depression, anxiety, and stress have serious consequences. Not only may psychological morbidity have a negative impact on a student’s academic performance and quality of life, but it may also disturb family and institutional life. Therefore, long-term untreated depression, anxiety, or stress can have a negative influence on people’s ability to operate and produce, posing a public health risk,” it said, underscoring the need for intervention programs.

“According to the findings of this study, high levels of depressive symptoms among college students should be brought to the attention of relevant departments. To prevent college student depression, relevant departments should improve the study and life environment for students, try to reduce the generation of negative life events, provide adequate social support for students, and improve their cognitive and coping capacities to improve their mental qualities,” it added, highlighting how “outcomes of this study provide an opportunity for academic institutions to address students’ psychological well-being and requirements.”

Who is the culprit, and do we have a solution?

Dr Srinivas Rajkumar T, Consultant Psychiatrist at Apollo Hospital, Chennai, explained that the pressure on students is “multidimensional.”

“On one hand, there is the intense competition for limited seats in professional courses, and on the other, the weight of expectations from family and society. Many students also lack healthy outlets for stress, and conversations around mental health are still stigmatised. This combination makes young people vulnerable when they feel they cannot cope or fail to meet expectations. In addition, for several years leading up to competitive exams, students often take a break from sports, arts, and other extracurricular activities—sacrificing the very outlets that could help them manage stress more effectively,” Dr Srinivas explained.

He explained that the very traits which help students enter premier institutes—perfectionism, competitiveness, and high self-expectations—can later become risk factors. Once surrounded by equally talented peers, many begin to feel ‘average’, while academic pressure, lack of sleep, isolation, and the stigma around seeking help further intensify the strain. For those who link self-worth only to marks, even small setbacks can be crushing, creating a pressure-cooker effect.

He emphasised that the crisis cannot be blamed on one entity alone. A rigid, exam-centric curriculum, an education system that prizes marks over skills, and parents projecting their aspirations onto children all add to the burden.

What is needed instead is balance: creating opportunities across streams, valuing diverse talents, and shifting from performance-centered to person-centered education. Teachers must normalise mental health conversations, parents should see children as more than ranks, and society must treat seeking help as strength, not weakness.

Recently, the Supreme Court has also stepped in to address the crisis. On September 6, 2025, it constituted a 12-member National Task Force (NTF) on student suicides and mental health, headed by former judge Justice Ravindra Bhat.

The panel, formed after petitions by parents of students such as Rohith Vemula and Payal Tadvi, has now appointed nodal officers in every state and Union Territory. The NTF has already received over one lakh survey responses—from students, faculty, parents, citizens, and mental health professionals—and completed institute visits in Delhi, Haryana, Karnataka, and Tamil Nadu.

Adding to this, Dr Nemthianngai Guite, Associate Professor at JNU’s Centre of Social Medicine and Community Health, points out how institutional culture itself plays a crucial role. “In JNU, suicides are extremely rare because our learning environment is structured differently. Attendance is not compulsory, assessments focus on discussions and critical thinking rather than rote learning, and teachers act as facilitators around a round table. This cordiality matters.”

Drawing from Durkheim’s classical study, she emphasises that suicide must be seen as a social phenomenon. “In India, family pressure is a powerful factor—success is linked not just to jobs but even social mobility through marriage. When excessive discipline and expectations are imposed, it can push students toward fatalistic outcomes.” She also notes how social media and self-imposed expectations amplify the stress, especially for those from disadvantaged backgrounds whose families pin hopes of upliftment on their success.

For Dr Guite, the solution lies in empathy and flexibility. “Human beings are not machines. Students need time to process, and unexpected crises must be met with understanding. Exams are not everything; learning should be enjoyable. As the Buddha said—Excess of anything is poison. The key is balance and support.” She adds that institutions must also work actively to break the stigma around seeking help, so that students feel safe accessing counseling or sharing their struggles without fear of judgment.

Despite several tragic cases seen across the country, millions of students are still left in a dilemma—caught somewhere between ambition and survival, expectations and self-worth. For Arijit, the harshest weight is not just the exams but how society treats those who falter. “The idea of failure is always looked down upon. That societal image itself crushes young minds and pushes many towards extremes,” he said.

Also Read: Student suicides soar in India as exam pressure takes a deadly toll