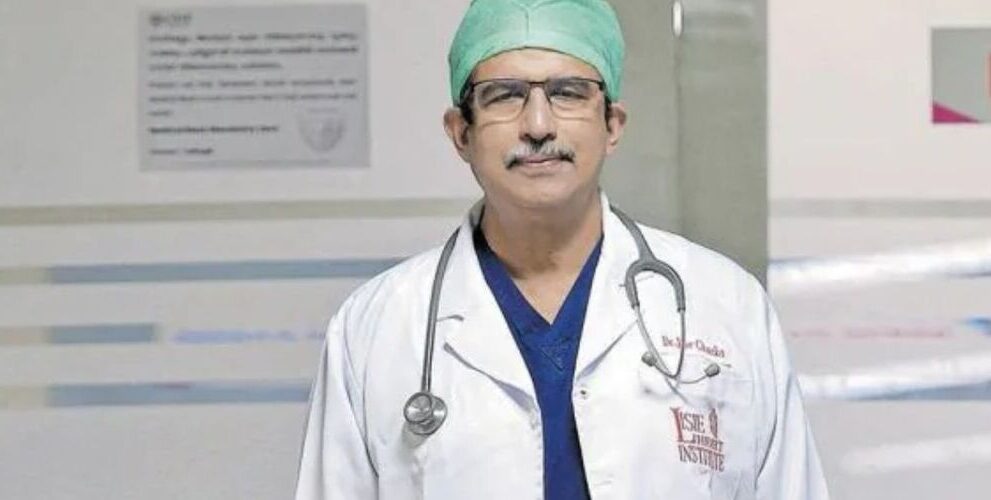

A heart for humanity: in conversation with Padma Bhushan Dr Jose Chacko Periappuram

Dr Periappuram, who was recently awarded the third-highest civilian award in India, talks about his journey in cardiac surgery that spans decades, marked by groundbreaking achievements

Author

Author

- admin / 12 months

- 0

- 6 min read

Author

On January 25, 2025, a day before the country celebrated Republic Day, Dr Jose Chacko Periappuram, one of India’s pioneering cardiac surgeons, received a phone call from a Secretary in the Home Ministry. It was a phone call that he probably would not forget any time soon—he had won the Padma Bhushan for ‘revolutionising surgical cardiac care in his state’.

Dr Periappuram told media that the call came as a surprise, even though he was aware that he was nominated; but for those who had followed his life’s work, it was a well-deserved recognition. The cardiac surgeon is a pioneer of his field in Kerala with over three decades of experience and is credited with performing the first heart transplant in the southern state.

First Check caught up with the doctor, after he was awarded the third-highest civilian award, to talk to him about his journey in cardiac surgery that spans decades, marked by groundbreaking achievements and an unwavering commitment to making healthcare accessible to all.

The soft-spoken doctor began the conversation by reflecting on his return to India in the mid-1990s after a decade in the UK. “When I came back to India to start my cardiac surgical career in 1995-1996, it was a great challenge,” he recalls. “In Kerala, there were no open-heart surgeries happening then. People had to travel to other states or nations for surgery. Even convincing patients to undergo bypass surgery here was difficult.”

This resistance did not deter him. Instead, it fueled his determination. “There’s a quote I remember, from my hospital director’s wall: ‘What stops you from going forward is not what is in front of you, it’s what is inside you.’ If you have a will, there’s a way.”

“Heart transplantation is not a commonly done procedure in our part of the world,” he says, recalling the early days. “There are multiple reasons for that, but initiating a program of heart transplantation is always a difficult proposition because it involves extensive organizational administration and great teamwork.”

In 2003, Dr Periappuram led the team that performed Kerala’s first heart transplant procedure. The journey to this milestone began in 2002 when he convinced his hospital administration and fellow doctors that heart transplants could save the lives of those with end-stage heart disease.

“These patients would die within a few months or weeks without a transplant,” he explains, his voice heavy with the weight of the countless lives touched by this initiative.

One of the most touching aspects of our conversation emerges when Dr Periappuram shares the story of his first heart transplant patient, Abraham. “He came to a medical camp we were conducting in Haripad,” he recalls, smiling at the memory. “When I told him about the possibility of transplantation, his response surprised me. He said, ‘Doctor, you can do it. I’m willing to have it done.’ His trust and motivation became the cornerstone of our transplant programme.”

When asked about the challenges of organ transplant procedures, Dr Periappuram delved into the complexities with characteristic thoroughness. “There are two types of organ donations,” he explains. “Live donation, where someone donates an organ they can live without, like a kidney, and cadaveric donation, which occurs after brain death.”

He emphasises that while organ donation rates have improved in India, they remain significantly lower than in countries like Spain, where about 35 people per million deaths donate organs, compared to India’s 0.5.

Heart transplants are done through cadaveric donations, and Dr Periappuram highlighted the critical timing involved in the complex procedure.

“A heart can’t be preserved for more than 4 hours,” he explains. “Within that time, you must transport it, bring it to the recipient, stitch it, and make it start working. It’s a marathon organization you need.” This constraint makes heart transplants particularly challenging compared to other organs like kidneys or liver, which can be preserved longer.

However, this means having tough conversations with families who have just lost their loved ones. The surgeon’s voice softened when discussing the emotional challenges of approaching families for organ donation.

“Most donors are young,” he says. “Sometimes, when we go for organ harvesting, we ourselves struggle emotionally. Imagine convincing a mother who has lost her only son in a tragic accident to consider organ donation. It’s incredibly difficult, but we try to help them see that their loved one can live on by saving others’ lives,” he adds.

In a heterogeneous society like India, varied cultural practices and religious beliefs present their own challenges when it comes to organ donation and transplants.

“Some religions believe in reincarnation and the need for a complete body in the next birth,” he cites. “However, most religions teach philanthropy, charity, and selflessness. Donating an organ is one of the greatest expressions of charity in our life.”

Financial costs associated with transplant surgeries are also a deterrent for some. “A hospital can perform a heart transplantation for as low as ₹5-6 lakhs,” he explains. “The actual cost, including surgery and immunosuppression for one month, typically won’t exceed ₹7.5 lakhs. Monthly medication costs start at around ₹20,000-25,000, reducing to about ₹5,000 after the first year.”

But Dr Periappuram has been working to help ease this financial strain too. In 2006, he established the Heart Care Foundation, channelling his expertise into social service. The foundation’s flagship project, “1000 hearts, 1000 lives, 1000 families,” has helped over 910 patients undergo heart surgeries in various government medical colleges across Kerala.

“We’ve assisted patients with nearly ₹2 crores worth of surgeries in the last nine years,” he states proudly.

The foundation also spearheads the “Save a Life, Save a Lifetime” program, teaching basic life support and CPR to the public. “If effective CPR is established at the right time, at least 30 per cent of people who would have died from cardiac arrest could be saved,” he emphasises. “When you save one life, you’re not just saving an individual; you’re saving an entire family.”

Interestingly, Dr Periappuram notes distinct differences between male and female hearts. “Physically, female hearts are smaller and have more delicate blood vessels, making surgery more challenging,” he explains. “However, female patients generally tolerate surgery better than males. Women also show greater emotional resilience in dealing with loss and stress.”

Looking ahead, Dr. Periappuram envisions a “Heart Village”—a comprehensive facility where cardiac patients can meet, share experiences, and access rehabilitation services, with an emphasis on preventive care. “Heart disease affects people in our society at least 10-15 years earlier than in the West,” he notes, with concern. “But most risk factors are preventable through lifestyle modifications.”

As our conversation draws to a close, Dr Periappuram shares his message for the public: “Lead a healthy life; stop smoking if you’re a smoker, exercise regularly, eat for life rather than pleasure, and monitor your cholesterol levels.”

Also read: Explainer: Cardiac Arrest and Heart Attack are not the Same – First Check

Do you have a health-related claim that you would like us to fact-check? Send it to us, and we will fact-check it for you! You can send it on WhatsApp at +91-9311223141, mail us at hello@firstcheck.in, or click here to submit it online.