Explainer: What BMI can and cannot tell you about your health

Author

Author

- admin / 2 years

- 0

- 3 min read

Author

Ideally suited for population-level studies, describing obesity by BMI can result in inaccurate assessment of adiposity.

By Florica Brahma

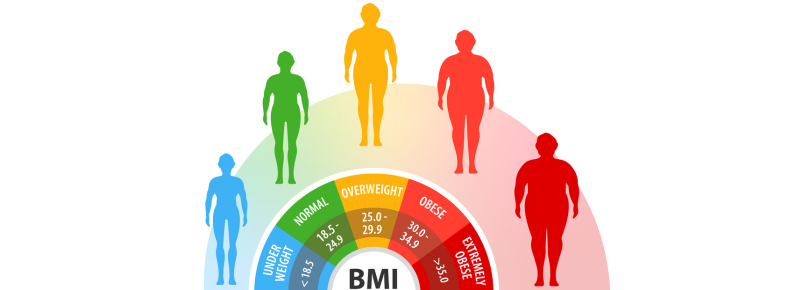

The Body Mass Index (BMI) is a metric system used to calculate body fat percentage by dividing one’s weight in kilograms by one’s height in meters squared. BMI = kg/m2. It was first introduced by Belgian mathematician and statistician Adolphe Quetelet in the early 19th century.

BMI offers a broad assessment of the health risks associated with obesity and aids in grouping people into categories, namely underweight, healthy weight, overweight, and obese. A BMI of 25 to 29.9 is considered overweight, while a BMI of 30 or higher is categorised as obese. A higher BMI is known to co-relate with a higher risk of developing several health problems, including chronic diseases such as heart disease and diabetes.

However, results of the global INTER-HEART study, show that BMI had only a modest association with myocardial infarction and it was not significant after adjustment for other risk factors. There is compelling evidence to indicate that regional fat distribution may be critical in determining the cardiovascular risk associated with obesity.

It’s important to recognise that BMI has its limitations and should be considered alongside other health indicators to obtain a more comprehensive understanding of an individual’s overall health status. It is pertinent to mention that BMI is based on the ideal numbers for an average Caucasian male. In other words, it may not provide an accurate picture for everyone, mainly women and people of colour.

As muscle weighs more than fat, a person with a higher muscle mass may have a higher BMI, even if they have a low body fat percentage. On average, women have 18-20% fat in their bodies, whereas men have only 10-15% fat.

BMI also doesn’t take into account other criteria, such as genetics, body shape and bone density. This means that a group of people may share the same BMI but may have different health outcomes.

Although BMI is ideally suited for population-level studies, describing obesity by BMI can result in inaccurate assessment of adiposity. The numerator in the calculation of BMI does not distinguish lean muscle from fat mass. Thus, a person with central obesity can have a normal BMI and yet will have a high mortality risk.

The visceral fat around our organs is not accounted under the BMI. Yet it is one of the biggest threats to our body. There is also a growing recognition of a ‘metabolically healthy’ obesity state, in which some individuals are free from the metabolic complications of obesity, most likely because of less visceral fat and preserved insulin sensitivity. It also does not take into account one’s fitness level as people with fit bodies generally tend to fall under the overweight section, much like athletes.

Despite being widely used, BMI has come under fire for oversimplifying complicated health issues and failing to take individual differences in body composition into account. Given that BMI does not measure body fat directly, it is prudent not to use it as a diagnostic tool.

(Medically reviewed by Dr Maulik Patel, First Check member and consultant physician from Gujarat, India.)