Latest

India’s growing anaemia crisis: Why millions are suffering from this preventable public health emergency

Anaemia is everywhere in India, and poses grave risks. However, many of us dismiss the symptoms of anaemia as "normal," which is at the crux of India’s anaemia crisis.

Author

Author

- admin / 4 weeks

- 0

- 11 min read

Author

Remember the times when a classmate fainted in the middle of a school assembly? Or the college days when a friend constantly complained of feeling dizzy and tired but brushed it off as “weakness”? Even today, in villages and small towns, women returning from childbirth are told to “eat more” when they struggle with fatigue. These everyday moments—so ordinary and so familiar—are often signs of anaemia.

Anaemia is everywhere in India, and poses grave risks. For instance, in Andhra Pradesh’s ‘Agency areas’, which are Scheduled areas that are primarily inhabited by tribal communities, a young woman, Reddy Suseela, succumbed after suffering fever and swelling. Villagers suspected a “mysterious disease,” but doctors clarified she was severely anaemic. In fact, officials estimate that nearly 90 per cent of people in these Agency regions are anaemic.

However, many of us dismiss the symptoms of anaemia—fatigue, dizziness or light-headedness, cold limbs, and headaches, among others—as “normal.” This normalisation is at the crux of India’s anaemia crisis. It is not a strange disease that strikes in isolation; it is a silent epidemic that has seeped into daily life across rural and urban India. From school children to young mothers, anaemia continues to claim lives and futures. Data from the National Family Health Survey (NFHS-5) shows rising prevalence across all groups—children, adolescents, and women—making anaemia one of India’s most pressing public health emergencies.

What is anaemia, and how prevalent is it?

Anaemia is a condition in which the number of red blood cells or the level of haemoglobin in the blood falls below normal, reducing the body’s capacity to deliver oxygen to vital organs and tissues. It can affect anyone, but women and children remain the most vulnerable groups.

In children, severe anaemia can impair brain development, motor skills, and immunity. In pregnant women, it increases the risk of maternal mortality, preterm birth, and low birth weight.

The most common cause is iron deficiency, throat infections, chronic illnesses, heavy menstrual bleeding, pregnancy-related complications, and genetic conditions such as thalassaemia also contribute.

Despite being both preventable and treatable, anaemia remains one of the world’s most widespread public health challenges. According to estimates, globally, it affects over 50 crore women aged 15 to 49 and close to 27 crore children under five years. This is approximately 40 per cent of all children under five years of age, 37 per cent of pregnant women, and 30 per cent of women aged 15–49 years, who are anaemic. It also accounted for an estimated 5 crore years of healthy life lost due to disability, with the leading causes being dietary iron deficiency, thalassaemia, sickle cell trait, and malaria.

The burden is heaviest in Africa and South-East Asia, which together account for more than 35 crore affected women and close to 19 crore affected children. India is not much better; in fact, the National Family Health Survey-5 (2019–21) shows that not only is our anaemia burden higher than global averages, it is also rising.

Among children aged 6–59 months, 67.1 per cent were found to be anaemic, up from 58.6 per cent found to be anaemic in the 2015-16 round. Similar trends are seen among adults too, with the report saying that the prevalence of the condition has increased “from 53 per cent in 2015-16 to 57 per cent in 2019-21 among women, and from 23 per cent in 2015-16 to 25 per cent in 2019-21 among men.” (sic.)

It showed that 57.2 per cent of non-pregnant women (15–49 years) and 52.2 per cent of pregnant women were anaemic, both higher than the previous rounds. Adolescent girls (15–19 years) were particularly affected, with nearly 60 per cent anaemic.

State-wise figures reveal how deeply entrenched the crisis is. “The prevalence of anaemia among children aged 6-59 months is highest among children in Gujarat (80 pc), followed by Madhya Pradesh (73 pc), Rajasthan (72 pc), and Punjab (71 pc). Several Union territories have even higher prevalence of anaemia—Ladakh (94 pc), Dadar & Nager Haveli and Daman & Diu (76 pc), and Jammu & Kashmir (73 pc). The states with the lowest prevalence of anaemia among children are Kerala (39 pc), Andaman & Nicobar Islands (40 pc), and Nagaland and Manipur (43 pc each),” according to the survey.

Among women, 60 per cent or more are affected in states such as Chhattisgarh, Bihar, Odisha, Gujarat, Jharkhand, Assam, Tripura, and West Bengal. “The prevalence of anaemia is also very high in the Union territories of Ladakh (93 pc), Jammu & Kashmir (66 pc), Dadra & Nagar Haveli and Daman & Diu (63 pc), and Chandigarh (60 pc),” the report added.

Even in states like Kerala, which performs better than others on many developmental indicators, more than one-third of its women and children were anaemic, showing that the problem cuts across geography, economy, and development levels.

What are the symptoms and causes of anaemia?

Anaemia can develop slowly and its symptoms often go unnoticed until they become severe. Common signs include persistent tiredness, dizziness, cold hands and feet, headaches, and shortness of breath, especially during physical activity. In more serious cases, people may show pale skin, gums, or eyelids, rapid heartbeat and breathing, dizziness when standing up, and an increased tendency to bruise easily.

The condition is diagnosed when blood haemoglobin levels fall below the thresholds set for age, sex, and physiological status. Importantly, anaemia is not a disease in itself but an indication of an underlying problem. Nutritional deficiencies are one of the leading causes, with iron deficiency being the most common. Inadequate intake or poor absorption of nutrients like vitamin A, folate, vitamin B12, and riboflavin can also contribute, since they play vital roles in haemoglobin production and red blood cell formation. Blood loss is another significant factor, whether from heavy menstrual bleeding, postpartum haemorrhage, or chronic losses due to parasitic infections such as hookworm or schistosomiasis. Babies born with low iron stores are also at greater risk.

Infections and chronic illnesses further complicate the picture. Diseases like malaria, tuberculosis, HIV, and intestinal parasites can either cause direct blood loss, impair nutrient absorption, or alter metabolism, leading to anaemia. Long-term inflammation and chronic conditions are also known to disrupt red blood cell production, resulting in anaemia of chronic disease. For women, gynaecological and obstetric conditions play a vital role, as consistent heavy menstrual losses, the expansion of blood volume during pregnancy, and blood loss during and after childbirth are common pathways leading to anaemia.

Additionally, in many regions, inherited blood disorders are a major cause. These include thalassemia, caused by abnormal haemoglobin synthesis, sickle cell disease, where the structure of haemoglobin is altered, and other haemoglobinopathies or defects in red blood cell enzymes or membranes.

A 2021 review further highlights the social and demographic dimensions of anaemia, showing it is not only a medical condition but also deeply shaped by socioeconomic circumstances. As the review notes: “It is known that some key social determinants, especially social and demographic factors such as a mother’s education, wealth index, and family size, can affect anaemia, which is socially patterned by education, wealth, occupation, and residence. Anaemia is a marker of socioeconomic disadvantage, with the poorest and least educated being at greatest risk of having anaemia and its sequelae.

Different studies claimed that iron deficiency anaemia is significantly associated with low birth weight, sex, age, rural residence, infectious disease, under-nutrition, poor socioeconomic status, household food insecurity and maternal-level factors like duration of lactation, poor dietary iron intake, poor educational status, and anemia among mothers. The population differences in the prevalence of anaemia are explained by environmental factors affecting nutrition, chief among these are ethnic customs and geographic considerations.”

Air pollution adds to the crisis in India

The World Bank reports that the entire population of India is exposed to unhealthy levels of ambient PM 2.5. Air pollution has emerged as a significant factor influencing anaemia rates in the country. Experts analysed satellite images of fine particulate matter (PM 2.5) across districts on the day preceding the National Family Health Survey IV and compared them with district-wise anaemia rates among children and women of reproductive age. The analysis revealed a clear correlation: for every 10 micrograms per cubic metre (µg/m³) increase in PM 2.5 exposure, the average anaemia prevalence rose by 10 pc among children and by 7.23 pc among women of reproductive age, according to studies published in Nature.

Further evidence comes from a study published in BMC Geriatrics, which highlighted an association between indoor air pollution—typically from the use of unclean fuel—and anaemia. This effect was more pronounced among elderly men, above the age of 45, compared to women of the same age group.

In examining the connection between air pollution and anaemia, industrial activity emerged as the largest contributor to PM 2.5 levels, followed by emissions from the unorganised sector, domestic fuel use, power generation, road dust, agricultural waste burning, and transport.

What can be done?

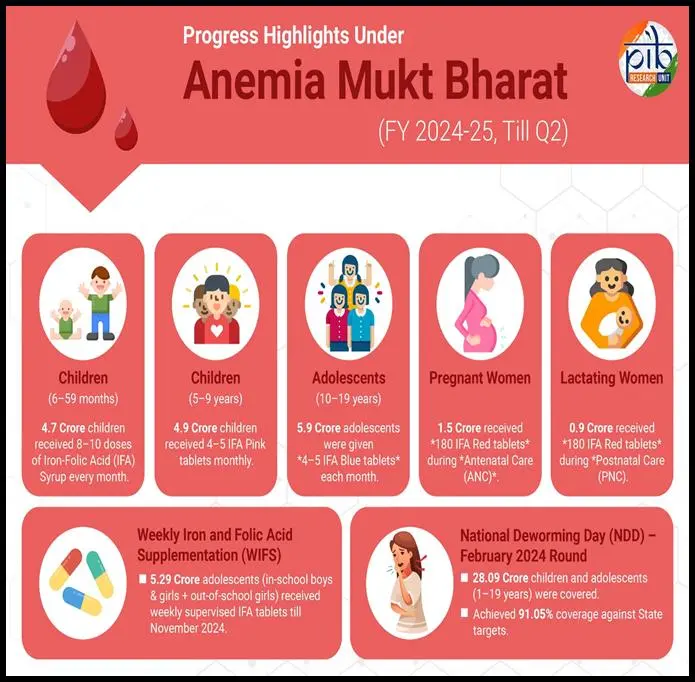

Although Anaemia Mukt Bharat, launched in 2018, focuses on iron-folic acid supplementation and fortified rice, there are some strategic gaps, as highlighted by a recent study. Without accurate estimates of anaemia’s true burden and its clinical causes, programmes risk inefficiency, with access, exclusion, and leakage remaining concerns. The review proposes a threefold strategy: first, a nationwide, district-level survey using venous blood instead of capillary blood samples to measure Hb and anaemia determinants; second, a food-based approach to improve dietary diversity and Fe bioavailability; third, revision of Hb thresholds and individualised supplementation strategies.

Another study highlighted the role of diet in India’s anaemia crisis. “Iron deficiency anaemia is a major public health concern in India and is widespread in different regions of this country. Nutritional iron deficiency, in particular, lack of sufficient consumption of heme iron and other dietary factors, are considered to play a role in the high prevalence of anaemia in India,” it reads.

To address this, the government launched the Diet and Biomarker Study India (DABS-I) in 2022, to understand the correlation between dietary patterns and prevalence of certain conditions, including anaemia, and in 2023 it was reported that anaemia-related questions were going to be dropped from the next round of the NFHS. The second phase of data collection began in 2024 for DABS, which is now expected to survey regarding anaemia.

Dr Gita Prakash, an Internal Medicine Specialist based in Delhi, also echoed that the rise of anaemia in India is largely linked to lifestyle, dietary habits, and socio-economic factors. She highlighted that in urban populations, many people follow restrictive diets, which often leads to reduced intake of essential vegetables and fruits. “A few of the vegetables and fruits which they should be eating, I think it goes down,” she said. Access to nutritious food is also a problem for lower-income groups, as healthy options are often expensive and limited.

She noted that working women face additional challenges. “There’s no time to really sit down and look at your meal… It’s quicker to make whatever is easy, and while they care for their children and family, they often neglect their own nutrition,” Dr Prakash explained. Menstrual health further compounds the problem. “Sometimes women bleed heavily or have frequent cycles and don’t reach the doctor in time. This continues for a while, leading more to anaemia,” she added.

According to Dr Prakash, most patients come to the hospital with fatigue, weakness, shortness of breath, pallor, headaches, and difficulty concentrating. She stressed that prevention starts with diet. “You should eat whatever is available at that time. If you don’t get spinach now, eat other green vegetables available in that season.” Supplements can also play a role, particularly for women who cannot maintain a balanced diet. She recommends basic iron supplements combined with folic acid and vitamin C to improve absorption, noting that these do not need to be expensive.

Dr Prakash emphasised that nutritional needs vary across life stages. Young girls should receive supplementation alongside a healthy diet, women post-childbearing must replenish nutrients lost during pregnancy and breastfeeding, and older women entering menopause should ensure their diet remains balanced to prevent anaemia.

“First thing is diet, then exercise, then making sure you eat the correct foods, reach the hospital when required, and get checkups regularly. If you are treated, you don’t have to take expensive medicines,” she added.

She also reassured that locally available vegetables, such as ghia, tinda, tori, and seasonal saags, provide essential vitamins and can effectively prevent anaemia without relying on exotic foods.