What’s on your plate? Study links Indian diet to diabetes and obesity

Indian diet and diabetes are critically linked, with a recent study revealing widespread high-carbohydrate, low-protein eating patterns driving a national health crisis of metabolic disorders

Author

Author

- admin / 4 months

- 0

- 8 min read

Author

In a comprehensive nationwide study, the Indian Council of Medical Research-India Diabetes (ICMR-INDIAB) has unveiled concerning trends in the Indian diet that correlate with escalating rates of diabetes and obesity.

The study, encompassing 1,21,077 adults across the country, highlights a significant dietary shift towards high carbohydrate consumption, particularly from low-quality sources, coupled with inadequate protein intake. These dietary patterns are identified as major contributors to the increasing prevalence of metabolic disorders in the country.

In India, over 60 per cent of all deaths are attributed to non-communicable diseases (NCDs), and this threat is growing with lifestyle and dietary changes. “The leading causes are cardiovascular diseases (27%), followed by chronic respiratory diseases (11%), cancers (9%), diabetes (3%), and other conditions, including obesity (13%),” according to official estimates. The crisis is so acute that the Prime Minister himself had spoken of “the need for nationwide awareness and collective action to reduce obesity” earlier this year.

Considering the risks of the rising obesity and diabetes epidemic in India, taking a closer look at dietary patterns becomes essential. Understanding what people are eating, in what quantities, and the quality of those foods is crucial to addressing the root causes of these metabolic disorders. The prevalence of high-carbohydrate, low-protein diets, excessive sugar consumption, and insufficient healthy fats is not just a statistic; it directly shapes the health outcomes of millions of Indians across all age groups.

What the study found

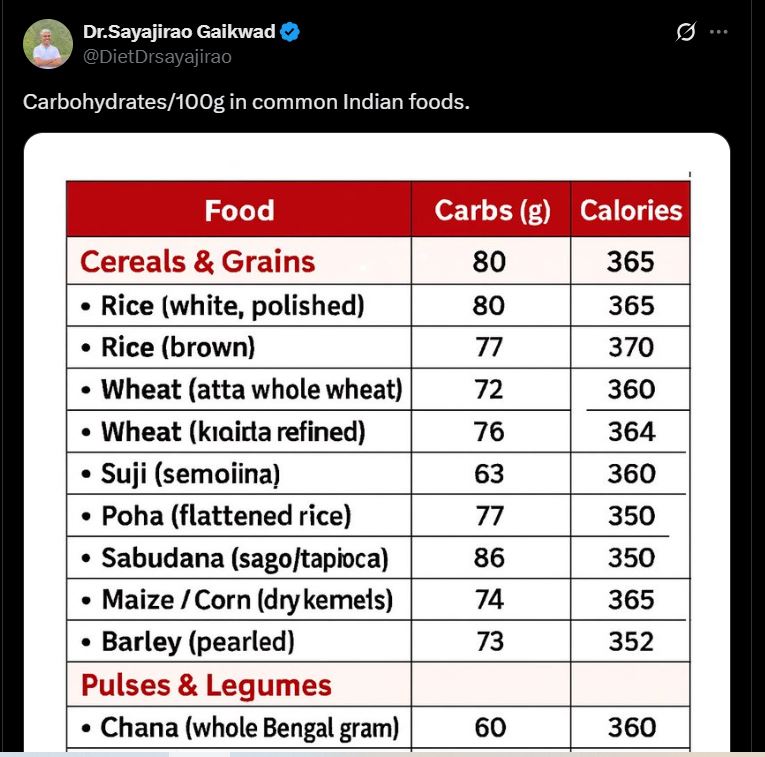

The ICMR-INDIAB study reveals that the average Indian diet comprises approximately 62 per cent carbohydrates, one of the highest proportions globally. This carbohydrate intake predominantly stems from refined sources such as white rice, milled whole grains, and added sugars. Regional variations indicate that white rice is a staple in the South, East, and Northeast, while wheat is more prevalent in the North and Central regions. Despite the popularity of millets, their consumption remains limited to only three states: Karnataka, Gujarat, and Maharashtra.

“Data from the current study along with previous surveys, confirm that Asian Indians consume high amounts of carbohydrates. Our results show that white rice is the most popular primary cereal staple (61% of population) followed by whole wheat flour (34%), with only a small percentage using millet flour. Because of the Green Revolution (introduction of high-yielding varieties of wheat and rice in developing countries, leading to major increases in the production of these foodgrains) in the 1960s, there has been a decrease in millet consumption, and an increase in rice and wheat consumption,” (sic.) it said.

Concurrently, the study identifies a concerning trend of low protein intake, averaging just 12 per cent of daily calories. Most protein sources are plant-based, including cereals, pulses, and legumes, contributing 9 per cent of daily energy. Dairy and animal proteins contribute a mere 2 per cent and 1 per cent, respectively. This suboptimal protein consumption is particularly pronounced in the East and Northeast regions.

The research also highlights excessive intake of added sugars, highlighting that India accounted for 15 per cent of the global sugar consumption, with 21 states and union territories surpassing the recommended limit of less than 5 per cent of total daily calories. Saturated fat intake exceeds the advised threshold of 7 per cent of total energy in all but four states – Jharkhand, Chhattisgarh, Arunachal Pradesh, and Manipur. Conversely, the consumption of healthier fats, such as monounsaturated and omega-3 polyunsaturated fats, remains low across the country.

The study shared that these dietary imbalances are strongly associated with an increased risk of metabolic disorders. The study’s findings indicate that higher carbohydrate intake correlates with a 14 per cent higher likelihood of newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes.

“In India, most whole grains are consumed as milled flour for flatbreads such as chapati and roti. Milling lowers the particle size of whole wheat and increases its glycemic index to the extent that the glycemic response becomes similar to that of refined wheat products and white rice,” it said.

Notably, substituting just 5 per cent of daily carbohydrate calories with plant or dairy proteins significantly lowers the risk of developing diabetes and prediabetes. However, replacing carbohydrates with red meat protein or fats did not yield the same protective effect.

“We were unable to evaluate the effect of replacing carbohydrates with foods other than plant protein, such as intact whole grains, fruits and vegetables, which are also high in fiber and have been shown to decrease the risk of NCDs. Further studies should investigate this in the Asian Indian population to inform more comprehensive nutritional policy recommendations,” it added.

Why it matters & what are the healthy choices you can make

The study highlights that owing to “rapid nutrition and epidemiological transitions over the past two decades,” the prevalence of NCDs have seen an alarming increase in the country. “The recent Indian Council of Medical Research–India Diabetes (ICMR–INDIAB) study, a national cross-sectional population-based survey conducted from November 2008 to December 2020, reported weighted (for region, age and sex) prevalence of type 2 diabetes (T2D) and prediabetes of 11.4% and 15.3%, respectively. The prevalence of generalized obesity and abdominal obesity was also high at 28.6% and 39.5%, respectively,” it said.

The situation is equally concerning among children and adolescents. UNICEF warns that, if urgent action is not taken, India could have the highest number of overweight and obese children globally within the next decade, with over 2.7 crore children aged 5 to 19 projected to be affected by 2030, accounting for 11 per cent of the global burden.

The public health crisis can also have great economic costs, with the study estimating a projected $839 billion price tag by 2060. “Given the enormous public health burden of NCDs and their associated economic costs, it is crucial to identify cost-effective, practical strategies for reducing NCD risk,” it adds.

Dr Rajiv Kovil, Head of Diabetology and weight loss expert at Zandra Healthcare, highlighted the deep-rooted cultural habits that contribute to India’s rising rates of obesity and diabetes. He explained that traditional Indian practices, such as counting chapatis per person during meals, unintentionally encourage excessive carbohydrate consumption. “If a person eats three chapatis, it is often considered insufficient, so more carbs are added around the plate. This cultural habit of ‘roti counting’ is worsening the problem,” he said. He advised that one simple way to break this cycle is to change the way meals are served. Non-carbohydrate items, such as salads, soups, dal, or non-vegetarian dishes, should come first, with carbohydrates making up only a third of the plate.

Dr Kovil also pointed out that modern lifestyles and fast-food culture have exacerbated the problem. “Many households today replace main meals with quick, high-carbohydrate options like poha, upma, sandwiches, or fried snacks. These are easier to prepare but significantly increase carbohydrate intake,” he noted.

He emphasised the economic aspect of food choices, observing that unhealthy street foods are often cheaper than healthier alternatives. “A fruit costs more than a vada or a samosa, so people opt for the cheaper, less nutritious option,” he said, urging that healthier foods should be made more affordable to encourage better choices.

Sweets, he added, are another major contributor. “In India, everything is celebrated with sweets – festivals, birthdays, promotions. Milk-based sweets, barfis, and other treats are culturally ingrained and lead to excessive sugar consumption. India’s per capita sugar consumption is already higher than the global average, largely due to these traditional practices,” he explained.

Addressing protein intake, Dr Kovil highlighted that most Indians consume insufficient protein, with plant-based sources predominating and dairy or animal protein contributing very little. “Ideally, people should consume at least 1 gram of protein per kilogram of body weight daily. Pulses, soy, paneer, and eggs are good sources, but traditionally vegetarian diets and infrequent consumption of pulses lead to chronic protein deficiency,” he said. He stressed that even a small increase in protein intake – 3 to 5% of daily calories can improve insulin sensitivity, hunger regulation, and overall metabolism, significantly reducing the risk of prediabetes and obesity.

He also stressed the importance of early education in nutrition. “If children learn about sources of calories and balanced diets at a young age, they develop healthier eating habits that carry into adulthood. Currently, many children celebrate birthdays with pizza and burgers, normalising high-carb, low-protein meals,” he said.

On lifestyle changes, Dr Kovil emphasised that diet alone is not enough. Regular exercise is essential to make muscle fibers more sensitive to insulin and improve metabolic health.

Also read: Type 2 diabetes may lead to debt, bankruptcy, foreclosure: Study

(Do you have a health-related claim that you would like us to fact-check? Send it to us, and we will fact-check it for you! You can send it on WhatsApp at +91-9311223141, mail us at hello@firstcheck.in, or click here to submit it online)