Is your old pressure cooker silently poisoning your food?

Experts advise replacing pressure cookers every 8-10 years, or sooner if damaged, and opting for safer stainless steel alternatives to protect your health

Author

Author

- admin / 4 months

- 0

- 6 min read

Author

Ever wondered if the old cooker sitting in your kitchen is quietly harming your health?

That’s the alarming claim made in a viral reel posted by Dr Manan Vora, an orthopedic surgeon with 556,000 followers on Instagram. The video has already garnered 236,000 views and over 10,000 shares.

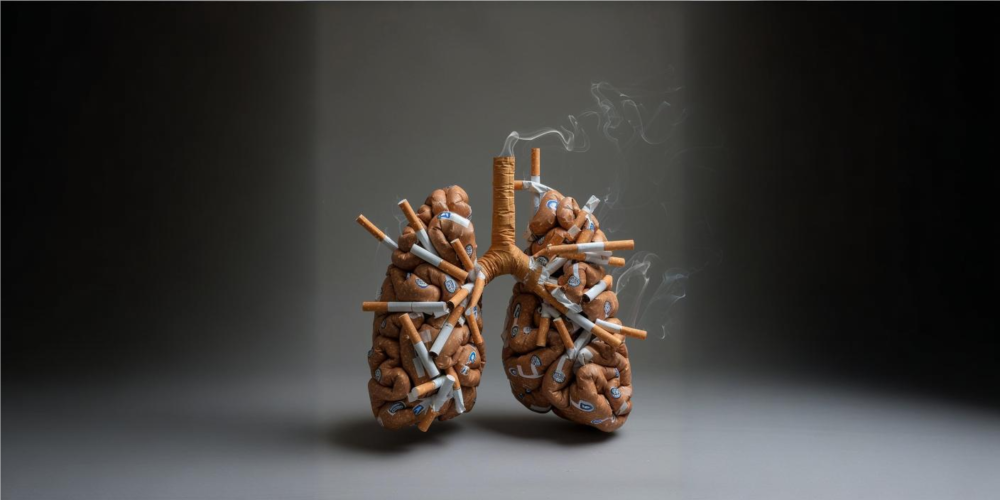

“Your old pressure cooker could be the most toxic thing in your kitchen. When your cooker gets old, it can leak lead into your food. It doesn’t leave your body easily. It slowly builds up in your blood, bones, and even your brain,” says Dr Vora in the video.

Is your old pressure cooker really poisoning your meals?

Several studies have highlighted that certain aluminium and brass cookware, including pressure cookers, can be a significant source of lead exposure. However, these seem to be primarily about the older cookers made of aluminium.

One of the first studies we found was from 1998, published in Science of the Total Environment, which found that lead leaching from Indian pressure cookers, particularly from components like safety valves and rubber gaskets, “can be significant.” “From the present study, it is clear that pressure cooker cooking introduces extra (lead) into the food material compared to ordinary vessel cooking. Pressure cooker cooking with tamarind leaches more (lead),” it said.

The study added that “looking at the very wide range of lead levels leached from various brands of pressure cookers, it certainly seems possible to keep the lead contamination to a minimum by proper choice of the materials used in the manufacture of these pressure cookers.” It also said that, at least for that time period, “Lead contamination of food by cookers is not very high when compared to the daily intake of lead from various food items consumed by the Indian community.”

However, in recent times, the scientific community has continued to flag the dangers associated with aluminium cookpots and pressure cookers. A 2022 study examined aluminium cookpots used by Afghan refugee families resettled in Washington State, who “have the highest prevalence of elevated blood lead levels (BLLs) of any other refugee or immigrant population.” Resettled families brought several lead-containing items from Afghanistan, including aluminium cookpots. The study’s objectives were “to evaluate the potential contribution of lead-containing cookpots to elevated blood lead levels in Afghan children and determine whether safer alternative cookware is available.”

Researchers screened 40 aluminium cookpots for lead content using an X-ray fluorescence (XRF) analyser and used a leachate method to estimate the amount of lead that migrates into food. They also tested five stainless steel cookpots to determine safer alternatives. The results showed that “many aluminium cookpots contained lead in excess of 100 parts per million (ppm), with a highest detected concentration of 66,374 ppm. Many also leached sufficient lead under simulated cooking and storage conditions to exceed recommended dietary limits. One pressure cooker leached sufficient lead to exceed the childhood limit by 650-fold.” In contrast, stainless steel cookpots leached much lower levels of lead.

The study concluded that “aluminium cookpots used by refugee families are likely associated with elevated blood lead levels in local Afghan children. However, this investigation revealed that other U.S. residents, including adults and children, are also at risk of poisoning by lead and other toxic metals from some imported aluminium cookpots.”

A follow-up study expanded testing, screening “an additional 28 pieces of aluminium cookware and 5 brass items for lead content using an X-ray fluorescence (XRF) analyser and used our leachate method to estimate the amount of lead that migrates into food.”

The results showed that “many aluminium cookware products contained in excess of 100 parts per million (ppm) of lead. Many also leached enough lead under simulated cooking and storage conditions to exceed recommended dietary limits. One hindalium appam pan leached sufficient lead to exceed the childhood limit by 1400-fold.”

“Brass cookpots from India also yielded high lead levels, with one exceeding the childhood limit by over 1200-fold. In contrast, stainless steel cookware leached much lower levels of lead,” the study added.

The researchers highlighted that “aluminium and brass cookware available for purchase in the United States represents a previously unrecognised source of lead exposure.” They also noted that childhood lead poisoning “is one of the most common pediatric (sic.) health problems worldwide, although lead exposures and resulting disease are almost entirely preventable,” and that “numerous studies have documented that low-level lead exposures can affect a child’s neurological development, with severe impacts on learning, intelligence, and behaviour.”

They also tested 17 additional stainless steel items as safer alternatives, and found that “In contrast, stainless steel cookware leached much lower levels of lead.” This is promising, because many newer pressure cookers in India are made of stainless steel.

In line with these findings, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) warns consumers and retailers not to sell or use certain imported cookware that may leach significant levels of lead into food. The FDA notes that “young children, women of child-bearing age, and those who are breastfeeding may be at higher risk for potential adverse events after eating food cooked using these products.”

Expert opinion:

In line with these findings, experts agree on the importance of careful cookware selection and maintenance. Mrs Anjali Gupta, Dietician at Dr Ram Manohar Lohia Hospital, explained the health risks of lead exposure from old or low-quality cookware. She said, “Lead can accumulate in the body over time. In adults, it may cause fatigue, weak nerves, memory problems, or mood issues. In children, it can slow brain growth and lower IQ. Lead is not safe—it also affects vital organs like the kidneys, heart, and reproductive system.”

She also pointed out the risks of cooking acidic foods, explaining that “acidic ingredients like tamarind or tomatoes can accelerate the breakdown of a cooker’s surface when cooked for long periods, causing metal particles to leach into food.”

On the precautions to take, she added, “In our kitchens, we prefer steel cookware for meal preparation. Ideally, pressure cookers and kadhai should be replaced every 8 to 10 years. If the whistle or rubber gasket isn’t working properly, it should be replaced immediately, because a malfunctioning cooker can be unsafe; we see such cases of cookers exploding every year.”

To reduce risks, she recommended, “Replace cookware that is scratched, corroded, or has peeling layers. Always check for scratches, black patches, or a damaged rubber lid, and replace the cooker if it’s in poor condition, even before 8 years.”

She advised focusing on quality while selecting cookware. “Steel is recommended, but make sure to go for the best quality available for better health,” she said.